Highlights:

Issue 8 - August 2025

Issue 5 Article 4

The Immortal Cells and their Ethical Legacy

25/5/20

By:

Lee Zhe Yu, Nathan

Edited:

Wu Yuxuan

Tag:

Cell Biology and Microbiology

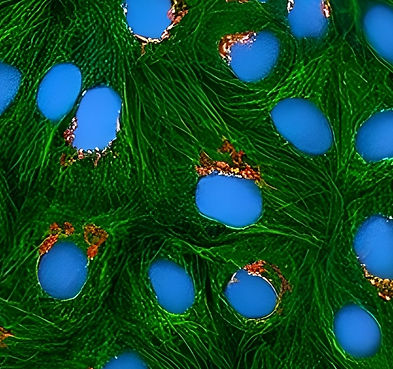

<Cover image: A HeLa cell culture>

“The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” premiered on HBO in 2017, starring Oprah Winfrey as the titular character’s daughter. While the film received generally positive reviews, it was by no means a major blockbuster. This begs the question of why a global star would be willing to shoot a television movie about a seemingly normal person many have hardly heard of. The catch was, Henrietta Lacks was no normal person.

The Unlikely Main Character

Born in 1920 to a poor African American couple, Henrietta Lacks was the 9th out of 10th children in the family. Her mother died when she was 4 years old, and with her father lacking the patience to raise his 10 children, the young girl was thus sent to live with her grandfather amongst relatives. In 1950, she felt a knot inside of her just before her fifth pregnancy and mentioned it to her cousins. However, she did not seek medical attention at that point in time. It was only until January 1951 after her fifth pregnancy when she sought medical attention at John Hopkins Hospital. There, she was diagnosed with cervical cancer. During her first cancer treatment procedure, while sedated on the operating table, the attending surgeon obtained two tissue samples from her, one from her tumour and the other of her normal cervical tissue. He then proceeded to carry out the procedure, involving the attachment of pouches containing radium to her cervix so that the radioactive activity of the radium could kill the cancerous cells. Unfortunately, even after switching to the more aggressive treatment method of X-ray therapy, the cancer had spread and engulfed her internal organs by September 1951. Within a month, on 4 October 1951, she was dead at the tender age of 31.

While this may seem like an unremarkable account of another cancer patient’s tragic demise, there was something unusual about this particular woman. The aforementioned tissue samples collected by the attending surgeon had been transferred to the head of tissue culture research at John Hopkins University, who had been aiming to develop an “immortal”, continuously proliferating cell line. At his lab, his team cultured both tissue samples, and was surprised when Mrs Lacks’ tumour cells were able to continuously proliferate at unprecedented rate, effectively achieving “immortality”. They would eventually play a key role in biomedical research, and be at the centre of one of the most contentious controversies in research ethics.

The Immortal Cells

Humans are not immortal, as demonstrated by Mrs Lacks’ own death. As cells divide, they have to replicate their DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid. DNA stores all the genetic information that determines an organism’s characteristics including humans. Each DNA molecule contains two strands, each with a 5’ end and a 3’. These DNA strands are antiparallel with each other as shown below.

Figure 1: Antiparallel DNA strand.

However, DNA polymerase, the enzyme [1] cells use to replicate their DNA, can only synthesise DNA in the 5’ to 3’ direction. Hence, there will be a leading strand which DNA polymerase can continuously synthesise the complementary DNA strand, and a lagging strand which the DNA polymerase has to bind to RNA primers before synthesising it. These DNA fragments are called Okazaki fragments. Afterwards, the gaps left by the RNA primers are sealed with another enzyme, DNA ligase, as shown below.

Figure 2: DNA replication. Topoisomerase helps to stabilise the DNA strand.

However, DNA ligase can only patch gaps between two DNA strands instead of holes. This leaves a hole at the end of the lagging strand, also known as a primer gap. Consequently, not all of the DNA is replicated, leading to a loss of genetic material and genetic information from the organism. If the lost DNA contains vital genetic information, the cell would be unable to carry out regular cellular function and hence die, effectively preventing cells from replicating. This is also known as the end-replication problem.

Figure 3: The end-replication problem, illustrated

To get around this loss of DNA, human cells have developed repetitive nucleotide sequences of TTAGGG at the caps of chromosomes, called telomeres. Telomeres are non-coding regions [2], hence the loss of these telomeric sequences (also called the shortening of telomeres) do not significantly affect normal cell function. This helps to maintain genomic stability of the cell, ensuring that daughter cells have the same genotype as the initial cell prior to cell division. However, since the telomeres have finite length, after a certain number of divisions, the telomere sequence becomes too short for the cell to undergo another cell division. This limit is called Hayflick’s limit, and is strongly correlated with ageing.

However, Mrs Lacks’ tumour cells were clearly able to survive indefinitely, long after their donor had died in 1951. In fact, as of 16 September 2024, HeLa (as these cells became known as) cells are still being widely used in science labs around the world. The secret to their apparent immortality is reliant on a ribonucleoprotein enzyme that is able to synthesise the TTAGGG repeats of telomeres. Named telomerase, this enzyme was able to effectively lengthen the telomeres of HeLa cells. In contrast with the typical cell, the HeLa tumour cells were able to avoid the end-replication problem by replacing the lost DNA segments. Consequently, they can bypass Hayflick’s limit and continue undergoing cell division indefinitely unlike normal cells, effectively achieving “immortality”.

A Larger-than-life Impact

As the first cells to have achieved effective “immortality”, many scientists proceeded to adopt HeLa cells as the human cell line of choice. Consequently, these versatile HeLa cells have contributed to numerous biomedical research projects which have greatly benefited mankind. HeLa cells have laid the groundwork for the polio vaccine, developed a cancer detection method so reliable that it is still used in research today, and was one of the pioneering space travellers, helping to gain insight to the impact of space radiation might have on human cells. They have also played an integral part in 3 Nobel Prizes, namely the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine on how certain viruses like human papilloma viruses can cause cancer, the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine on the discovery of telomeres and telomerase, and the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry on the development of a microscope technique allowing live-viewing of ongoing cellular process like cell growth.

With such a short lifespan of 31 years, it is remarkable Mrs Lacks managed to have an outsized contribution to biomedical research, benefitting the lives of many individuals, most of whom were born after her own death.

The means (always) justify the ends…?

There was a very important caveat, however. Mrs Lacks and her family did not know her cells were being taken and grown in research laboratories across the world. At the time of Mrs Lacks’ initial cancer procedure, hospitals were not legally required to obtain patient consent for using their tissue samples for research, and it was common practice then for physicians to do so. This included the acquisition of the two tissue samples from Mrs Lacks’ during her first procedure. During that time, the family was largely uneducated and sickened by poor living conditions; they lacked understanding of such practices nor had been informed of it. It was only until 1973, 22 years after Mrs Lacks’ death, when a family member learnt about the use of Mrs Lacks’ cells. Up to that point, they had not been compensated in any form for the use of Mrs Lacks’ cells, and it is hard to see if the research carried out up to that point had any direct benefit for Mrs Lacks’ family. Hence, the family claimed that they had been unfairly treated then.

While this argument may hold merit now, in 1951, there was no standard protocol regarding the collection of cells for research. Hence, the actions of the John Hopkins researchers who developed the HeLa cells were technically legal. It is hard to attribute any wrongdoing to them, especially given the fact that they, too, led modest lives, had impoverished upbringings, and gave away their HeLa cells for free. They were likely driven by idealism rather than entrepreneurialism. As an institution, Johns Hopkins itself has acknowledged that although it was common practice to collect tissue samples from patients regardless of race, such practice is no longer legally and ethically acceptable in the modern day with the addition of local and national regulations regarding tissue sample collection.

Enter the Corporation

This perceived unfairness prompted the Lacks family to take legal action, not against John Hopkins, but the biotechnology company using HeLa cells to develop treatments. In 2021, they filed a lawsuit against the biotechnology company Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. for unjustly enriching itself off HeLa cells. It further claims that the company received an estimated $26 million US Dollars of profits from using HeLa cells while the Lacks family themselves was struggling financially.

To summarise both sides’ arguments for simplicity, Thermo Fisher argued that the case should have been dismissed as the statute of limitations has expired. This was because more than 3 years since the alleged offence had taken place, and according to the Maryland Courts and Judicial Proceedings Statute 5-101, “a civil action at law shall be filed within three years from the date it accrues”. With the suit filed in Baltimore, a city in Maryland, the law would hence apply to the case. In addition, the Lacks family was considering their legal options long before the actual suit was filed. The company also alleged that it was against the convention of Maryland courts to allow a charge of unjust enrichment to proceed without an accompanying charge for tortious conduct, rendering the complaint invalid as there was no accompanying charge of tortious conduct.

However, the Lacks family contended that such an argument was invalid due to the company continuing to benefit from HeLa cells despite knowing that the cells were unknowingly taken from Mrs Lacks. They also contended that Thermo Fisher willingly took part in the unjust enrichment behaviour despite knowing that it could potentially be a violation of Mrs Lacks’ rights. The two parties eventually reached a settlement in private, in what was described as a “fitting day for [Henrietta Lacks] to have justice” by her grandson Alfred Lacks Carter Jr.

Balancing individual protections and communal gain

The case of Mrs Lacks highlights the importance of scientific promise being followed with proper procedure to safeguard individual rights. While the rest of the world benefited from groundbreaking technologies and various corporations received millions from developing treatments developed from her cells, Mrs Lacks’ family continued to live in poverty, with their health compromised by poor living conditions.

Today, there are stringent guidelines regarding informed consent across the world, like the US Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 Part 50.20 stating that “no investigator may involve a human being as a subject in research covered by these regulations unless the investigator has obtained the legally effective informed consent of the subject or the subject's legally authorised representative”. This means that participation in scientific research studies should be voluntary and the individuals involved are willing to do so.

Singapore’s equivalent is the Human Biomedical Research Act 2015, in which Part 5 Section 25 states that “no human biomedical research can be conducted if the appropriate consent of a person for participation as a research subject, including the use of his or her biological material or individually‑identifiable health information, has not been obtained”. Part 6 Section 38 of the same act goes a step further by considering “compel[ling] another person against that person’s will to allow his or her tissue to be removed from his or her body” and causing someone to allow the removal of tissue from his or her body “by means of deception or misrepresentation” as an offence. As explained by National University of Singapore researcher Dr Markus Labude, “tissue may be taken from a person only with the appropriate consent of that person” and must be voluntary, with the “firm stance against commercialisation of human tissue” in line with existing legislation. This effectively outlaws the actions carried out by the John Hopkins scientists, considering that Mrs Lacks did not know that her tissues were going to be used for scientific research.

Now, the requirement to obtain the legally effective informed consent of individuals for research is a central protection provided for under the Health and Human Service regulations. This is founded on the foundational ethical principle for respect for individuals, requiring that they be treated as autonomous agents that deserve the opportunity to choose what should or should not be done to them. Today, a research investigator must actively share information about the research study with his or her prospective subjects and allow them to freely decide whether to enroll in the research study. Were Mrs Lacks' case to happen in our modern day, the John Hopkins researchers would have to share information about the purpose of their scientific research, the procedures involved during the study process, the potential risks involved and the potential benefits she may receive when carrying out the study to Mrs Lacks. They would only be able to take her tissue samples after obtaining her legally effective informed consent. In fact, more than 60 years after the initial procedure, Johns Hopkins helped broker an agreement between Mrs Lacks’ family and the National Institute of Health to allow biomedical researchers controlled-access to the whole genome data of HeLa cells.

As science progresses, it is imperative that ethics and law catch up in order to appropriately regulate the behaviours of scientists so as to unfairly disadvantage individuals which may have become unwitting test subjects. Now, with stringent regulations regarding informed consent in place, the next evolution would be to reduce the complexity of informed consent practices for everyone to easily understand the study that they are agreeing to participate in. Even so, as we look back and gripe about the perceived injustices the doctors or the biotechnology companies may have committed and went away unpunished, we should take pride in our progress. This, rather than being a statement on our failures to protect individual rights, is a reflection of the advancement of our collective understanding of bioethics from previous generations.

Endnotes:

1: Enzymes are proteins that facilitate chemical reactions in order for the body to carry out its various functions.

2: Such DNA regions do not code for amino acids, hence are not directly involved in protein formation.

References:

https://ontosight.ai/glossary/term/The-Telomeric-Sequence---TTAGGG

https://osp.od.nih.gov/hela-cells/significant-research-advances-enabled-by-hela-cells/

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v32/n11/cathy-gere/dying-and-not-dying

https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/henrietta-lacks-thermo-fisher.pdf

https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-A/part-50/subpart-B/section-50.20

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henrietta-lacks/upholding-the-highest-bioethical-standards

https://law.nus.edu.sg/sjls/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2024/07/2207-2016-sjls-mar-194.pdf

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.mdd.500650/gov.uscourts.mdd.500650.20.1.pdf

Image Credit:

Latest News